[su_vimeo url=”https://vimeo.com/273589168″]

B

C

|

|

D

E

Transcription

(START RECORDING – 00:00:00)

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: This is going to be a simple class in the sense that it’s not going to be one subject. It’s a collage. It’s a collage of ideas that I’m weaving together, but it’s one simple point. The one simple point is the Rebbe’s view on the touch of what a person does to everything in Judaism. To a certain degree, how it gets redefined by the human touch. I’m going to walk you through multiple different talks and ideas of the Rebbe until we realize how the Rebbe believed in it in so many different worlds of thought. From Torah to mitzvoth to Jewish law, the Rebbe has such an affinity to what the human touch is about and how precious the human touch is in G-d’s eyes that it overrides other dimensions of yiddishkeit because of the human touch.

I want to just give you a little bit of history and see in storylines in Jewish history how other scholars faced such challenges and talk about the human touch. So I’ll tell you an interesting story that I read recently and it’s a beautiful story. We Bostonians connected to the history of the Soloveitchik family which has been a blessing for Bostonians to have that great of a personality that considered Boston his residency. His grandfather was R’ Chaim Soloveitchik, one of the biggest scholars and the head of the yeshiva of Brisk. His grandfather, in the late 1800s, early 1900s, was one of the great, great personalities in the Lithuanian Jewish world. His works on the Maimonides was famous. His scholarly writing on the Talmud was famous. He had two sons. One of them is R’ Moshe who was the father of Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik, the Bostonian Soloveitchik and one was R’ Yitzchak Zev, the Griz he was called. Two sons he had.

One day, to R’ Chaim Soloveitchik’s home, two Chasidic Jews travelling business, not clear why they were travelling, came as guests to his office. As newcomers to town, they entered R’ Chaim Soloveitchik’s home. A law of Torah, that when guests come, you welcome them, you make them comfortable. That’s basic Jewish law. He called in his son, the Griz and he said to this son, so see if the Rebbetzin, referring to his wife, is at home because if she’s at home, I want to bring them over to eat something. They’re travelers. As he’s saying this to his son, the two Chasidic guests look at each other and they shmeichel, they give a smile to each other. As if what he just said was entertaining. When the son left the room, he looked at the two guests and said can you tell me what was so entertaining about me asking my son to go see if my wife’s home to make for you a meal. What’s so entertaining?

Without saying who the Chasidic Rebbe was — the story is told in the world of Brisk and they won’t say who these Chasidim were, from which camp they came from. They said you should know, that by our Rebbe, a couple of weeks ago, we ended up travelling and we came back and when we entered his office and when we were talking to him, all of a sudden he says oh, my wife came home. Let’s go, I want to serve you a meal. How did he know his wife came home? We walked across two streets and we went to his house and that’s what happened, his wife just came home. He says my Rebbe has prophecy and has the ability to know, he doesn’t have to send his son to find out when. That’s what these two Chasidim said to R’ Chaim Soloveitchik, the Brisker Rav. The Brisker Rav looked at them and said you’re right. This was his expression. He said siyata dishmaya, which is Aramaic, meaning G-d’s assistance happens to every person in what they want in their life to be important. If you truly are one and connected to the will of G-d, G-d knows what you consider important. Therefore, he assists you. I find it important and ask G-d’s assistance in the study of Torah and that’s where he assists me. Other things, I don’t call upon G-d to assist me. That was his response.

So sit back for two seconds and analyze what just happened here. The Chasidic master used G-d’s assistance for a person, to help a person in a simple thing of eating a meal. Hungry people. R’ Chaim says what’s essential to me is my knowledge of Torah and that’s where G-d assists me. The movement moving into the human relationship side of Judaism, understanding its significance in the most simple touch of serving somebody a meal and finding G-dliness in it versus taking the established G-dly routines, a mitzvah, learning Torah. Those are established G-dly routines that are set up in the system. But here you step a little bit outside the system where you’re turning to figure out human to human. Just on a human touch level. Serving somebody a meal becomes a G-dly act that you find that your assistance from G-d should be invested into that. You start sensing how the Chasidic movement was going this way a little bit and they started to move their way.

Let me give you another beautiful example. I pull these storylines from outside of the Chabad world so you get a picture and a sense of the greater pictures. One of the great Lithuanian schools in Russia was Slutzk. It was a great school in the city of Slutzk run by a man by the name of Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer. A brilliant man; he wrote a sefer called the Even Ha’ezel. He wrote it on Maimonides. He built one of the greatest schools in Slutzk in the early early 1900s. In the 1930s, late ’30s, the change of the tide, he picked himself up and moved to Israel. A famous man to us because one of the greatest orthodox communities today in America is in a town in New Jersey called Lakewood New Jersey. Who was the founder of Lakewood New Jersey, which by the way is made up of 50-60,000 Jews. It’s huge. There’s a Chabad house in Lakewood New Jersey. It’s an amazing city that has become an unbelievable enclave of orthodox Jewry. Who’s the founder? R’ Aaron Kotler. Who was R’ Aaron Kotler’s father-in-law? Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, this great leader from Slutzk, who took him as a son-in-law in the 1920s in Slutzk. Back then.

When the whole turnover was taking place in Europe, Rabbi Kotler came to the States as a son-in-law. Rabbi Meltzer, his father-in-law, moved to Israel. Something very interesting happened with Rabbi Meltzer in his last 20 years of his life in Israel. He lived until the late ’50s. What happened was he took on a little bit of a liking to the Chasidic movement. He lived in Tel Aviv. In Tel Aviv, there was a Slonimer Rebbe. The Slonimer Rebbe was the Weinberg family, a great Chasidic dynasty. It goes all the way back to the Baal Shem Tov’s times, this Weinberg time. The Slonimer Rebbe’s name was Avrohom Yehoshua Heschel Weinberg. Avrohom Yehoshua Heschel was the Apter, was a disciple of the Baal Shem Tov. By the way, Avrohom Yehoshua Heschel from the Conservative Movement is a direct descendant of him as well. That’s why his name is Avrohom Yehoshua Heschel. This Weinberg family was connected to the Apter. That’s why his name was Avrohom Yehoshua Heschel Weinberg. That was his name. He was the Slonimer Rebbe for the city of Slonim in Russia. He survived the Holocaust and made it to Israel. The Slonimer Rebbe, together with Isser Zalman Meltzer — Isser Zalman Meltzer used to walk by the Slonimer beis hamedrash. He used to walk by the house of prayer of the Slonimer Rebbe and he loved their nigunim. Then he would sometimes walk by on Friday night and there was a tish so he would walk in and sit and listen. He loved the ruach, the whole spirit of the room. It was a whole different spirit than what he was used to from a yeshiva world of academia, to all of a sudden a room of people swaying and singing and unity and oneness. It was transforming to him. It was an unbelievable experience.

When the son-in-law came to visit, R’ Aaron Kotler came to visit it, he didn’t like this new direction that his father-in-law was leaning towards. It wasn’t his cup of tea. All of a sudden his father-in-law was taking a liking and he would come home singing a nigun that he heard in Slonim. He didn’t enjoy it. R’ Aaron Kotler wasn’t a person who held back words so at a Friday night table, he said to his father listen, I think you have to remember where your roots are. I think you have to remember who you represent and the history of Lithuanian Jewish knowledge. These little detours are not — his father-in-law looked at him and said R’ Aaron, I want to tell you something. When it comes to an argument in Maimonides, I have to listen to you because when it comes to Maimonides, understanding a Maimonides in the world of academia, you’re a giant and you have a right to argue with me over Maimonides. But when it comes to understanding the soul of a Jew, shh. Allow me to understand that. Don’t interrupt it.

Again, you see all of a sudden, a whole movement of thought. That you start talking the relationship out of this G-dly structural design where all of a sudden it’s about learning. It’s about doing a mitzvah. Yes, it’s about that without question, but there’s another whole dimension that comes into play. In that dimension, it’s about the human touch. It’s about how you understand the uniqueness of the human being.

Audience Member: So can I go back to the story of the two Chasidim visiting him when they said that their rabbi would know that his wife was home, the answer by Soloveitchik was that he wanted to know Torah.

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: He wanted to use G-d for the study of Torah. He could find out about his wife. Why do I need to call upon G-d to tell me if my wife’s home to make the meal or not. I’ll send my son.

Audience Member: So the two Chasidim were really being disrespectful.

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: You know what, we’ll give outside commentaries along the way. How does that sound? Right now, leave the story as it is. To me, it’s more of a lesson and the moral of the story than getting involved in each one’s personal agendas. I can’t figure everybody out.

Let me now, for a second, move you into the Rebbe and how the Rebbe started to take this concept of what the Chasidic movement was doing and actually begin to internalize it on multiple levels. Through teaching. In the Chabad world today, 24 years after the Rebbe’s passing, which is like I just said, going to be in two weeks from now. The Rebbe said a famous Chasidic discourse that he offered to go public and to print it public the last Shabbat before he had a stroke in 1992. After he had a stroke in ’92 until he passed away, there was nothing that he authored. It was physically impossible to author. This Chasidic discourse became very famous. It’s like the last Chasidic discourse that we received from the Rebbe. The Rebbe actually built this Chasidic discourse on a discourse of his father-in-law. His father-in-law said this discourse in 1927 on Purim. When he said this discourse on Purim, this was in the throes of communism. He was sitting in Moscow and he said I know that there are people in this room that are part of the Yafsexia (ph), which was like the KGB. He said I know you’re present and I know you’re listening to me and I know whatever I’m going to say is going to go back. I’m not scared of you. I’m going to say what I have to say. This was a famous Chasidic discourse where he said that. That Chasidic discourse that he said in 1927 in Moscow got printed for the first time in 1951. Purim, 1951, approximately a month after he assumed leadership after his father-in-law’s yahrzeit, he puts out this Chasidic discourse from his father-in-law.

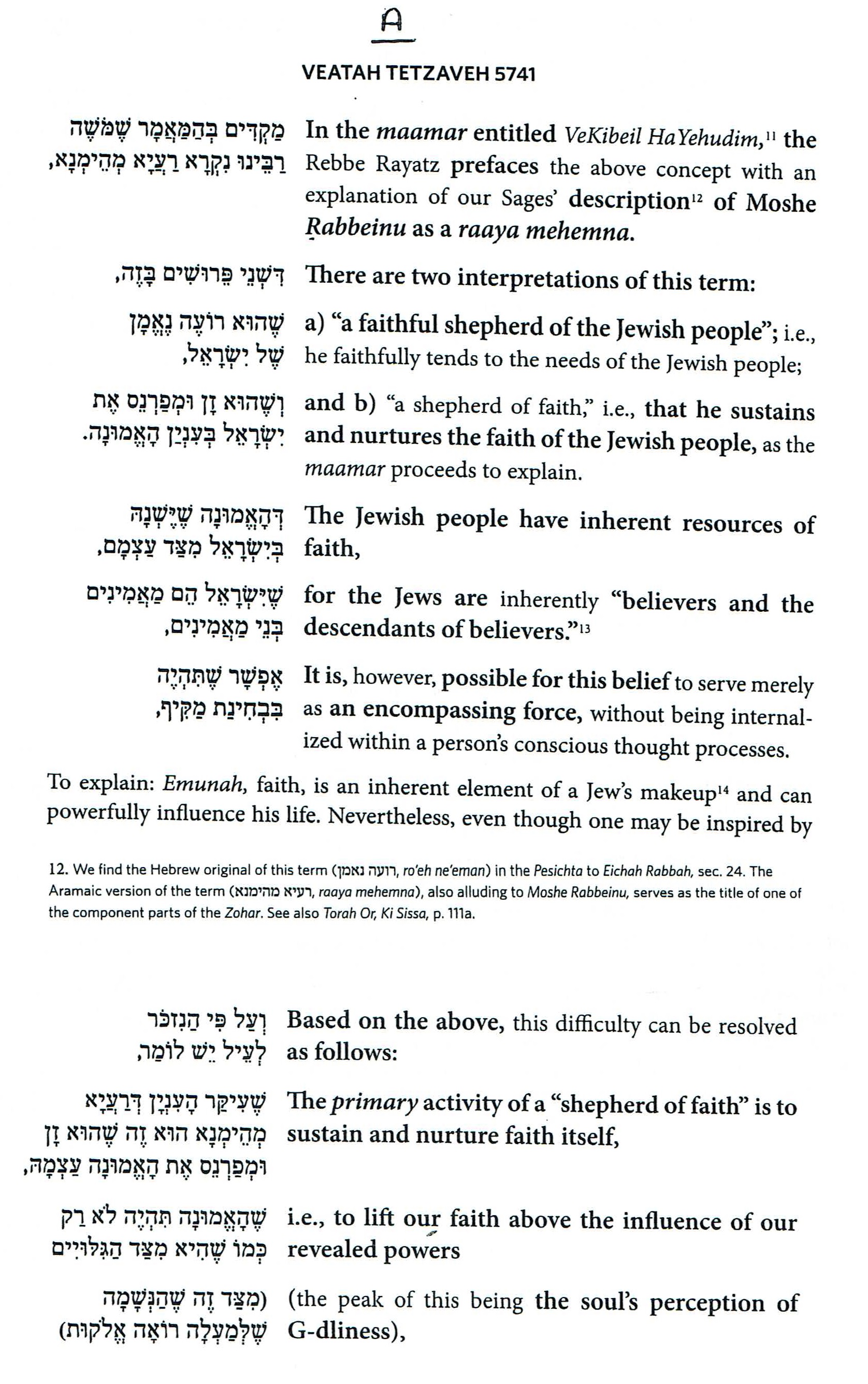

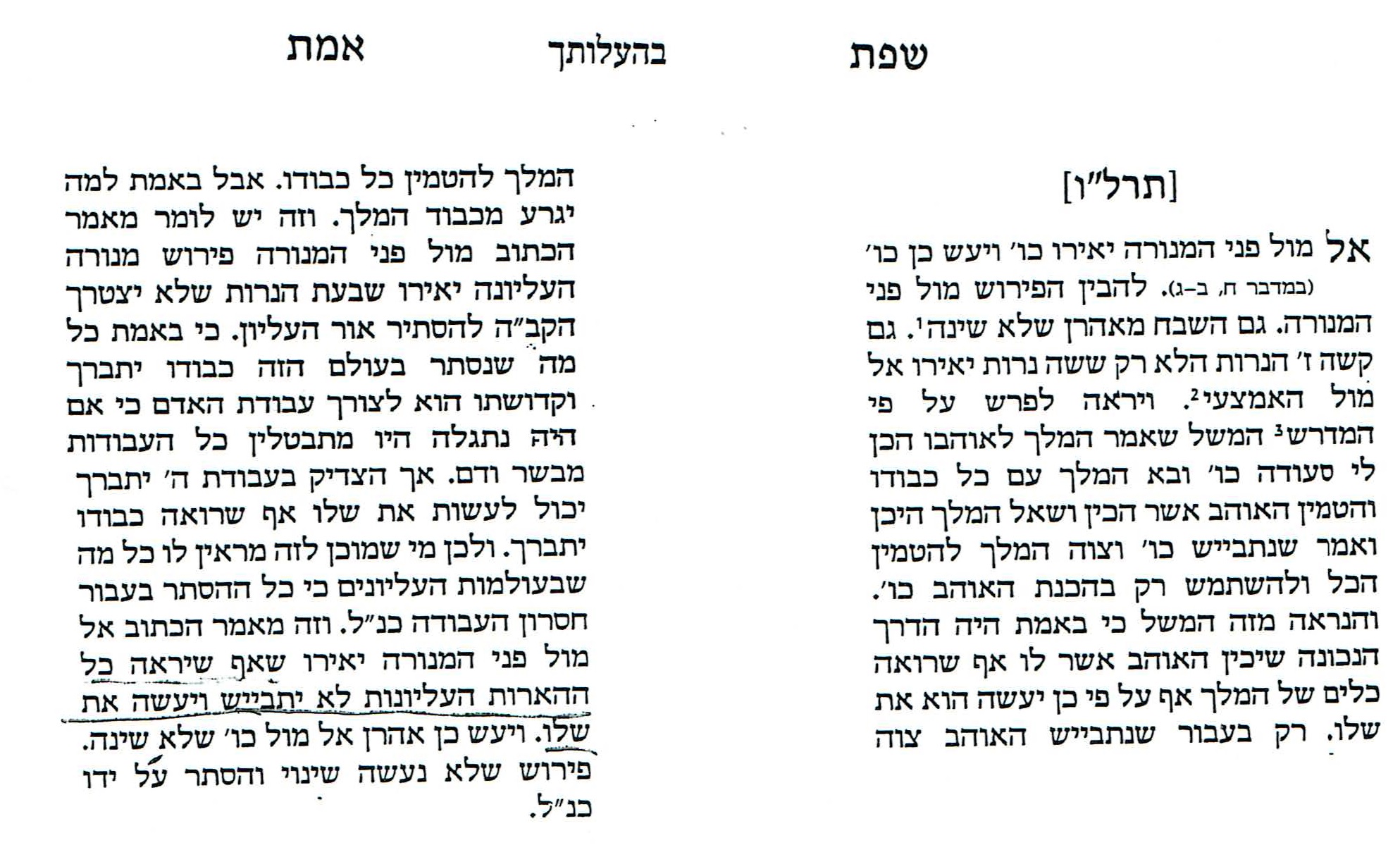

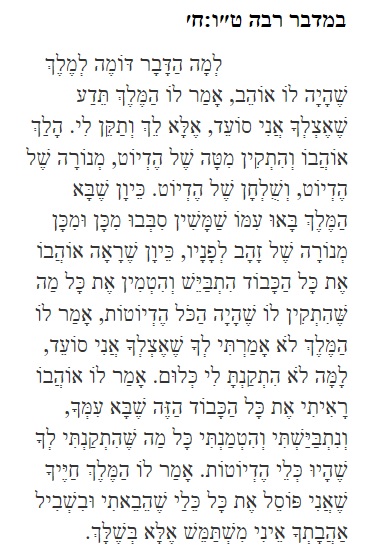

The Rebbe then based that last discourse that we have off of that Chasidic discourse. In the beginning of the Chasidic discourse — and I actually copied it for you — the Rebbe enters into a conversation about a very famous term that I’ve mentioned multiple times in this class, but I never actually printed it that you can actually see the language of the Rebbe. The Rebbe says — you can look at it. It’s my A on Page 1. The Rebbe starts out saying that I want to work this Chasidic discourse through what my father-in-law said at that famous 1927 gathering. He explained a term that is famous, a title for Moses. Moses was called raya mehemna. This is a description of Moses. Look at Footnote 12, which is important. The term raya mehemna actually begins with the roots in a Midrash. The term raya mehemna is Aramaic for a shepherd, a faithful shepherd.

The term actually begins in Midrash and the Midrash doesn’t use Aramaic, it uses Hebrew. What’s the Hebrew for it? It’s a Midrash in the beginning of Eicha. The Midrash refers to Moses as a ro’eh ne’eman. A faithful servant. No multiple interpretations to that. That is simple. The Midrashic view is that why Moses was called a faithful servant. He did his work faithfully. Let’s just develop that. The Midrash is simply saying a very simple thing. Moses’ relationship with his job wasn’t rational. He was committed to it on all levels with pure faith in the Jewish people. Therefore, the term raya mehemna is a terminology that is defining Moses.

Along comes the Zohar and the Zohar turns it a little bit. By turning it, it means uses Aramaic language which opens up this term to another meaning. The Zohar says raya mehemna. Along comes the Zohar and explains what it means. Moses shepherd to the Jewish community faith. The Jews struggled to believe in G-d beyond their comprehension. Along comes this great leader who shepherds faith to the Jewish people. He’s not a faithful shepherd in the way the Midrash sees it, in its natural meaning, that it’s a term about Moses. No, this is actually a term about the Jewish people. That you should know, he shepherd faith to the Jewish people.

The Rebbe spells it out. If you look at this thing, a faithful shepherd of the Jewish people or he shepherd faith to the Jewish people? It’s not a play on words. It’s two fundamental differences. One is the basic Talmudic interpretation and the basic Talmudic interpretation is Moses there’s Midrashim all about how G-d saw Moses as a faithful shepherd. It’s all about the uniqueness of Moses. Along comes the Zohar and adds a spiritual twist. What’s the spiritual twist? It’s not a term about Moses being a faithful shepherd. It’s Moses shepherding faith to the Jewish people. It’s a whole spiritual relationship of the Jewish people with G-d that the Jewish people should have this higher than natural, higher than intellectual, higher than just basic obvious relationship with G-d. Faith represents this inner deeper relationship with G-d. Talmud. The obvious concept of Moses being to the Zohar, to the spiritual.

By the way, if you go through the commentaries about this, this is exactly how it runs. There was two aspects to Moses. Moses being a faithful shepherd, it’s a term in Moses. Or Moses shepherding faith. It’s about the Jewish people gaining a relationship with G-d that only by such a leader could they ever fathom to have that unfathomable touch of a relationship with G-d. those are the two basic interpretations and the Rebbe’s father-in-law in that Chasidic discourse sticks with these two interpretations and presents — based on this theme, he goes on to build other ideas off it.

The Rebbe, a paragraph or two later — and I’m not going to walk you through what the Rebbe does because it’s impossible in an hour and a half to tell you how the Rebbe gets here. I want to get you to the Rebbe’s third interpretation to a faithful shepherd. The Rebbe turns around after two or three paragraphs and says now, if you agree with what I’ve said, the term, the concept of a faithful shepherd is a whole different meaning. Look at the bottom paragraph.

“The primary activity of a shepherd of faith is to sustain and nurture faith itself.” A third meaning in a faithful shepherd. Not that he’s a shepherd that is faithful, not that he shepherds faith. You know what he does? He shepherds to faith. He takes the mitzvah of faith to a place that the mitzvah itself couldn’t go. G-d gave us an obligation to believe in him. Read the books. It’ll tell you what the obligation’s made up of. Then along comes Moses and shepherds to the mitzvah of faith and says here’s the human touch. When the human being takes hold of this mitzvah, if he’ll take the mitzvah to a place that the mitzvah on its own doesn’t go. The mitzvah on its own cannot go based on its definition. The only reason why now faith can go to a place where it’s beyond its own limitations is because the human being is taking it. It’s another whole conversation the Rebbe enters here with. It’s not about a definition of Moses, that Moses is a faithful shepherd. It’s not about a definition of the Jewish people that he shepherds faith to the Jewish people. It’s a third definition. The third definition is he’s shepherding to faith. Moses becomes a shepherd to the mitzvah. By Moses taking a whole of the mitzvah, he takes the mitzvah to a place that out of the essence of his being, he carries it to a level of identity that the mitzvah on its own couldn’t be. It’s the interaction of the human with the mitzvah. From the Rebbe’s perspective, all of a sudden, in that interaction, the mitzvah gains from the human touch. That in its natural context, it couldn’t reach there.

I’ve always used this example, right or wrong. I don’t think (inaudible) ever fathomed that he’ll be that popular to what the Rebbe has done with it. Putting it on the streets, airports, the hair. Jews throughout the world — there isn’t a Jew that will not say to you somebody didn’t ask me to put on tefilin or a candlestick Friday night. I don’t think the candlestick Friday night ever fathomed. It’s this quiet little candlestick in your home. Someone asked me in the center of town, hello, are you Jewish, do you want to light a Friday night candle and give you a candle. The Rebbe is talking to the mitzvah. He’s not only talking to people that are going to do the mitzvah. He’s looking at the mitzvah and saying to the mitzvah I am going to take you to a place and put you into the psyche of people beyond what you ever fathomed that that’s what your purpose is. The average mitzvah of tefilin, what it fathomed of the Jewish law. You know what the Jewish law says? You wash your hands in the morning, you make your blessings, you go to synagogue, you prepare, you put on a talis. Then you finally come to putting on your tefilin. You stand in synagogue and be respectful. Don’t talk in your tefilin, don’t eat in your tefilin. Then take it off. Kiss it, put it back in the bag and it’s all beautiful. Well, welcome to 5th Avenue Manhattan. Running to work, washing hands who’s talking about, talis who’s talking about. On it goes, off it goes. You said a blessing, you’re on the run. You’re talking. But you know what? You put on tefilin. And it will stay with you forever. The pair of tefilin never fathomed that that’s what he was going to be used for. It’s not in its natural context. Read the code of Jewish law. That’ll tell you exactly what the natural context for a pair of tefilin is all about. Not on 5th Avenue while a guy is jogging.

The Rebbe is speaking not only to us, he’s speaking to the mitzvah. He’s looking at the mitzvah and saying to the mitzvah I want to take you to a place that you never fathomed you’ll go. That’s the Rebbe’s translation in raya mehemna, a faithful shepherd, shepherd’s faith or shepherds to faith. He’s talking to faith and telling faith where I want to take you as a mitzvah, which faith on its own would have never gone there. That’s a major part of that last Chasidic discourse of the Rebbe where the Rebbe turns around and identifies an unbelievable truth about the power of the human touch and how the human touch is not just by accident. It’s essential. It’s not only essential. It’s essential for the mitzvah that the human will touch.

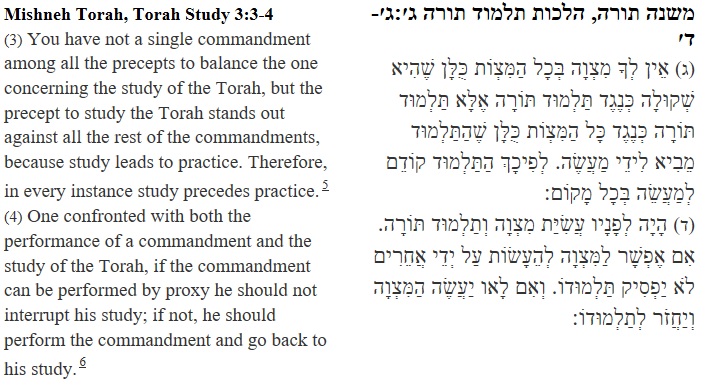

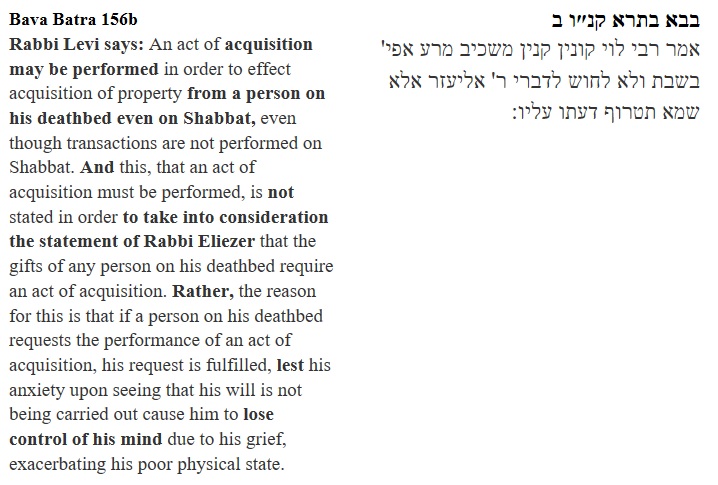

Let me move on to the next example. The Rebbe at a varbrengen, Yud Tes Kislev, 1954. The whole conversation about the uniqueness of the teachings of mysticism over the teachings of mussar. The whole Lithuanian movement of rehabilitating people’s character traits. The Rebbe goes into this conversation about a complication about Torah. Listen to the complication. What I did was — the Rebbe quotes actually the two Talmuds, but I quoted — it was just easier. I brought down Maimonides. In the laws of learning Torah, Chapter 3, Law 3 and Law 4. Law 3, ein lach mitzvah b’chal hamitzvos kulan shehi shekula keneged Talmud Torah. Ela Talmud Torah keneged kal hamitvzos. There’s no single commandment that is like the study of Torah. The study of Torah is equivalent to all the mitzvoth. Study precedes practice. What a great law. Because in this law, what is Maimonides saying? You can have somebody who needs something desperately, but you have the right to ignore because that’s only one mitzvah. Study of Torah is all the mitzvos. Why would I go give up 613 to fulfill one? It doesn’t make sense.

Law 2, haya lefanav asiyas mitzvah v’talmud Torah. Let’s say one is confronted with both the performance of a commandment and the study of Torah, im iy efshar l’mitzvah la’asos al yedei acherim, if it’s possible for others to do the mitzvah, he should learn. He shouldn’t break up his learning. But if there’s no one else to do the mitzvah, then you have to — why? That’s only one mitzvah. I’m going to stop learning which is 613. But Maimonides all of a sudden in the second law comes back and seems to contradict himself from the first law. In the first law he lays out that the study of Torah is 613, it’s the entire mitzvos. But then he comes back in the second one and says, but one second. Even though it’s the 613, I want to tell you something. That when there’s a mitzvah that no one else can do, you’ve got to stop learning and do it although it’s only one mitzvah. So I’m stopping 613 for the sake of one mitzvah.

The Rebbe asks a question. How do you make this work? The Rebbe goes into a beautiful interpretation. Here it goes. There is Torah within its own reality. G-d created the world and when G-d created the world, he said I created for the Jews and for the Torah. It’s a Midrash in the beginning of Genesis. Torah is an expression of G-d that has nothing to do with us human beings. Therefore, to a certain degree, even the angels said give us the Torah. All the kids sing the song. The angels wanted the Torah. It’s a Talmud in the tractate of Shabbat that the angels argued don’t give it to human beings. Torah is an expression of G-d independent of anything. Then comes Torah, the Rebbe says, when a human being touches it. When a human being studies it, that Torah goes beyond the Torah in its natural context.

As G-d gave the Torah and how the angels wanted it, it should never hit the human world and it should never come into the finite world, that’s an expression of G-d. That type of Torah, the Rebbe says, is equivalent to the 613. Then comes the human being and all of a sudden blurs the Torah and draws that Torah down into this world and takes it to a place that it could never go because of the human touch. When that human being does that to the Torah, it’s beyond anything. But at the same time, it can’t contradict the existence in the world. Therefore, if there’s something happening that only that human being can do, that human touch — because either adds to the Torah beyond it, it’s at the same time, that human touch that tells you you need to do something for another person. So within the human touch, it takes the Torah to reality. That the Torah on its own, in its natural context is equivalent to everything. It has accumulated everything in it. But when it goes into the human touch, the human touch takes it to a level of the Torah which is beyond its own existence. Although in its own existence, it’s equivalent to 613, now it’s beyond it. In that beyond it (inaudible) looks at the Torah and says help someone else at this moment if no one else is there to help and it supersedes the existence of the Torah.

In walks the Rebbe and turns around and demands of us to understand the uniqueness of the human touch not only talking about faith. We’re talking about the Torah, G-d’s wisdom. In G-d’s wisdom, there’s a reality of its natural existence and in G-d’s wisdom there’s a reality when the human being takes hold of it. When the human being takes hold of it, it takes it to a place that the Torah on its own can’t go there.

The Torah on its own will look at another person and say one second, I’m 613. I represent anything. You were asking me to do something, it’s just one thing. Then along comes a human being that’s doing it and when the human being takes a hold of the Torah, all of a sudden it can talk to the Torah and say to the Torah that this need at this moment is greater than your existence. Therefore, I’m going to interrupt my learning in order to do what’s needed in existence. That’s the human touch that has a right to change the dynamics of what the Torah’s about. Maimonides has no problem, two laws back to back.

There are two different dimensions of the Torah. The first law is the Torah in its natural context and in its natural context, it’s 613. The second law is about how the Torah is being now defined through the human experience. In that context it’s an entirely different reality. Here goes the Rebbe. I’m just putting together a collage for you. Here goes the Rebbe moving into the world of Torah study and showing you again what human touch is about.

This Shabbos in shul, I didn’t do it justice entirely and I want to do it justice. I want to show you again the Rebbe’s touch on an idea which is pretty powerful in its natural layout. What’s the idea. It’s intriguing how the Torah sets itself up. The Torah sets itself up in the Book of Numbers, Bamidbar. The first portion, Bamidbar, tells us of how the Jews are in the desert. It’s the first year of Jewish existence. The Torah was given. Moses is down from Mount Sinai. The Jews did the first sacrifice of the Passover sacrifice properly for the first time. This is a very unique experience for the Jewish community. This is before the 12 spies. We have no problems so far. The Jews are fathoming that they’re in Israel in a couple of weeks. It’s just a question of getting their act together and moving on. Moses inaugurates — for a week he works the temple as a trial test run and then the Tabernacle begins to function for real. When does the Tabernacle begin to function for real. Rosh Chodesh Nissan, before the first Passover. How does the Tabernacle function for real? It’s the inauguration of the 12 tribes. That’s the whole portion of Naso, the second portion. The 12 tribes each won a day and go into the portion of Naso in the Book of Numbers. It’s the most repetitive portion you’ll ever have. Because the Torah spends precious space repeating what each tribe did each day with their sacrifices, the gifts they brought, the celebration, the head of the tribe. It was a party each day for a different tribe. And they celebrated. Can you imagine, there were 12 days of pure celebration. You’re witnessing the concept of G-d being part of your existence, taking hold, because you saw how the sacrifices were being burned from heaven, you saw how the bread stayed fresh. You were seeing the hand of G-d. G-d said I want to reside amongst you. In those 12 days it was unbelievable. The whole community had firsthand experience.

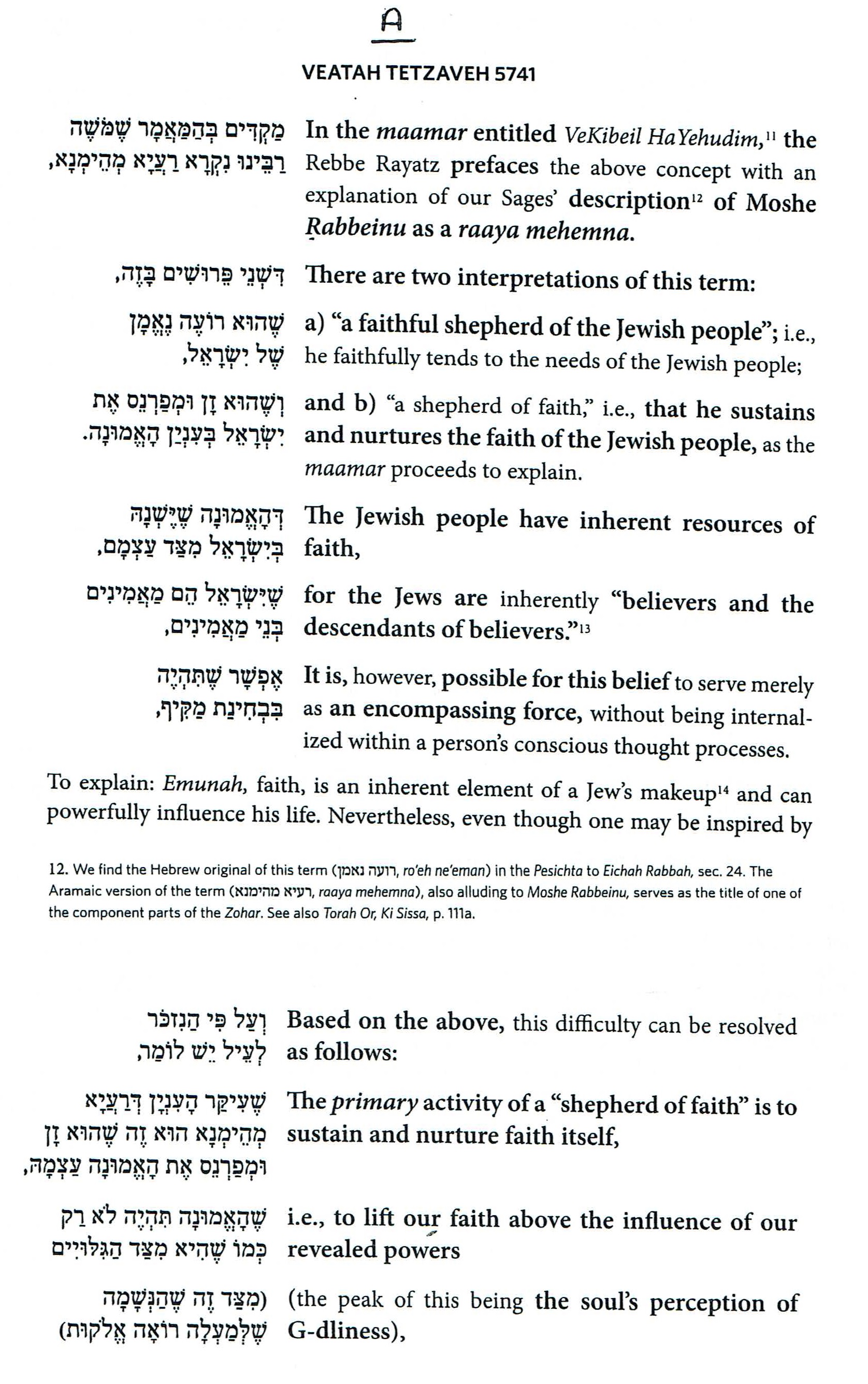

Then we come to the third portion, Beha’alotecha. The Torah transitions out of that story of 12 tribes’ celebration, 12 days and it goes to a story that Aaron should light the candelabra. What’s the connection? To a certain degree — this is the world of psychology here. There are multiple connections being made here. Aaron felt very humbled from the 12 tribes celebrating and dancing. When they’re all over and they leave, what is he doing? He’s lighting a menorah. No celebration. No sacrifices. No gifts. He’s standing there lighting a menorah. It was a little big perplexing to Aaron. This is the 13th day, hello, here I come. What am I left with? The menorah to light.

The Midrash opens it up even greater. To the Midrash, it goes into this theological dilemma. Not just psychologically of how he was contrasted to the tribes. It goes into a whole theological dilemma that they were having. There was so much light of G–d’s descending and there was so much pure spiritual bliss of G-dliness, his little menorah lighting in the midst of that unbelievable G-dly descent into this beautiful home. It’s almost like a person lighting the candle in a room that’s flooded with sunlight. What’s the purpose. It’s totally unnoticeable. So why do you walk around with a candle making believe that your candle is lighting the room. There are windows from all four sides and the sun is shining. You need a candle to walk around to light the room? Make a point that his little candle of yours is giving light. That’s how Aaron felt. What about lighting a menorah in this room. What’s the whole purpose of a menorah in this room. That’s the Midrash that goes one step beyond the human psychology of him being contrasted to the 12 tribes and opens it even wider. He was struggling over here with this greatest issue.

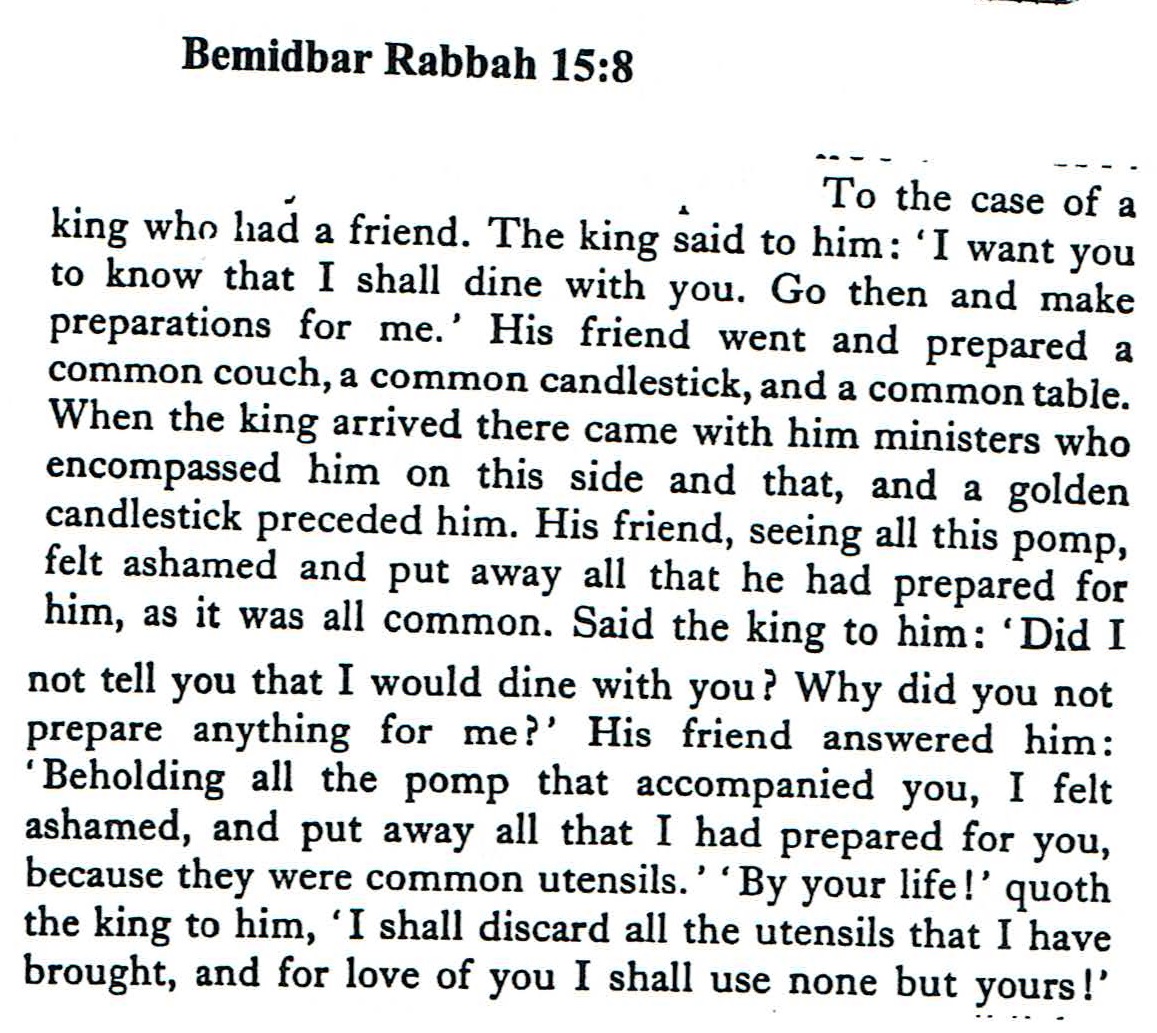

The Rebbe comes back with an example to try to help us understand how Aaron gets out of his persona little storyline in contrast to people and his personal little storyline in contrast to the bigger issue. Listen to the Midrash’s example. I didn’t do it service on Shabbos because when you say a story and a parable and you’re not hacking it home, people can misalign the two and then I feel like you missed the point as well. Here goes the Midrash. It’s my C on Page 2.

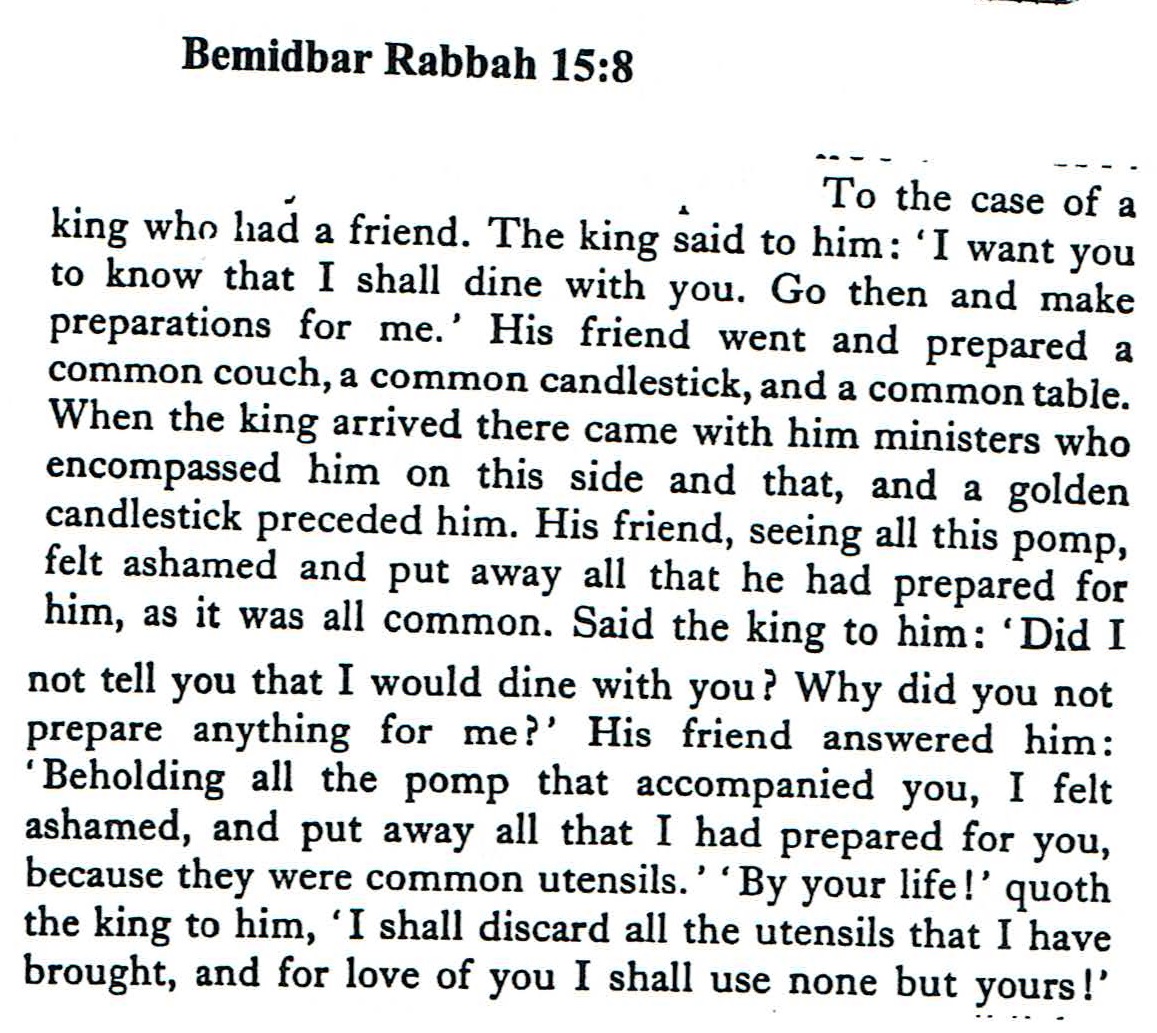

Lema hadavar dome, how can I help you understand Aaron’s dilemma and how he got over the dilemma. L’melech shehaya lo oyev amar lo hamelech teda she’etzlecha ani so’ed. One day, the king informs his best friend, I plan to eat dinner with you. Halach (inaudible). This best friend quickly goes to his house and sets up a bed. But he’s a poor man so it’s not the Waldorf Astoria. It ends up being the Ramada Inn type of a bed. One of those little beds, a cot. V’shulchan shel hedyot. Then he sets up a table. What does he have on the table? He doesn’t have china and wine goblets. He has some paper cups with paper fork and knife and he puts it out. And the food is simple. Kevan sheba hamelech b aim meshamsam, when the king arrives, he comes along with a whole entourage. They quickly realize, oh my god, the king is walking into this very low class room so what do they do? They quickly set up candelabras in the room, they quickly remove his food from the table. They remove his paper plates and they reset the entire room with Andrew catering. They bring in a caterer. It’s not schmaltz herring. This is we’re talking about really preparing a meal for the king.

What does the friend do? He realizes oh my god, I’m embarrassed so he quickly starts hiding everything he prepared that the king shouldn’t even notice that he put out schmaltz herring and the king shouldn’t even notice that there are paper goods in the house. The king shouldn’t even notice the cot that he set up for the king. He hides everything. This is the Midrash. Amar lo hamelech lo amarti lach she’etzlech ani so’ed. Did I not tell you that I want to eat with you? Lama lo hiscamta li klum, why didn’t you prepare anything for me? The friend turns around and says I witnesses all the greatness and your entourage and what they’re laying out for you. Nisbayashti, so I’m embarrassed so I hid everything. The king turns to him, amar lo hamelech, chayecha she’ani posher es kal kli shehe’veisi, I’m not interested in the goblets and what they have set up for me. U’bishvil ahavascha eini mishtamesh ela b’shelach, and because I love you, I only want to use yours. With that, the Midrash ends. What happened is irrelevant.

To the Midrash, the important thing is that the king informed him I want yours. That carries the day. The last thing we know about what the friend did was hiding everything. That’s the last thing we know what the friend did. What happened at this point? It’s not relevant. The key thing that the Midrash wants us to end with, knowing that G-d desires what we give. How it happens is not relevant. The impression the Madras leaves us with is the person in his own psyche is embarrassed. The person, out of his own nature, is putting everything away. In the bigger picture of things, what G-d has compared to what we have is infinite. But you know what? G-d will figure out how to eat my herring. Because he wants it. It’s what he wants. I personally don’t know why he wants it. I personally am hiding it. But he wants it and that’s how the Midrash ends. G-d turns around and says I want it. Which is by the way the psychology of Judaism for years. What’s the psychology of Judaism? Listen, whatever you do, don’t hold yourself too big about it because it’s not really about you. What is it about? It’s about G-d. why does he want it? I don’t know. He wants it. With that, just go with that.

Therefore, to a certain degree, what we do is humbled. It doesn’t have the value because we’re not asked to give it value. We’re asked to put ourselves aside. And in putting ourselves aside, we just simply accept the fact that G-d wants it and with that we live. That’s how the Midrash ends. The Midrash doesn’t even turn back to say oh, one second, the guy felt better about himself. One second, the guy actually went ahead and put out a beautiful meal. No. it’s not important. What’s important to the Midrash is the punch line, that G-d wants it.

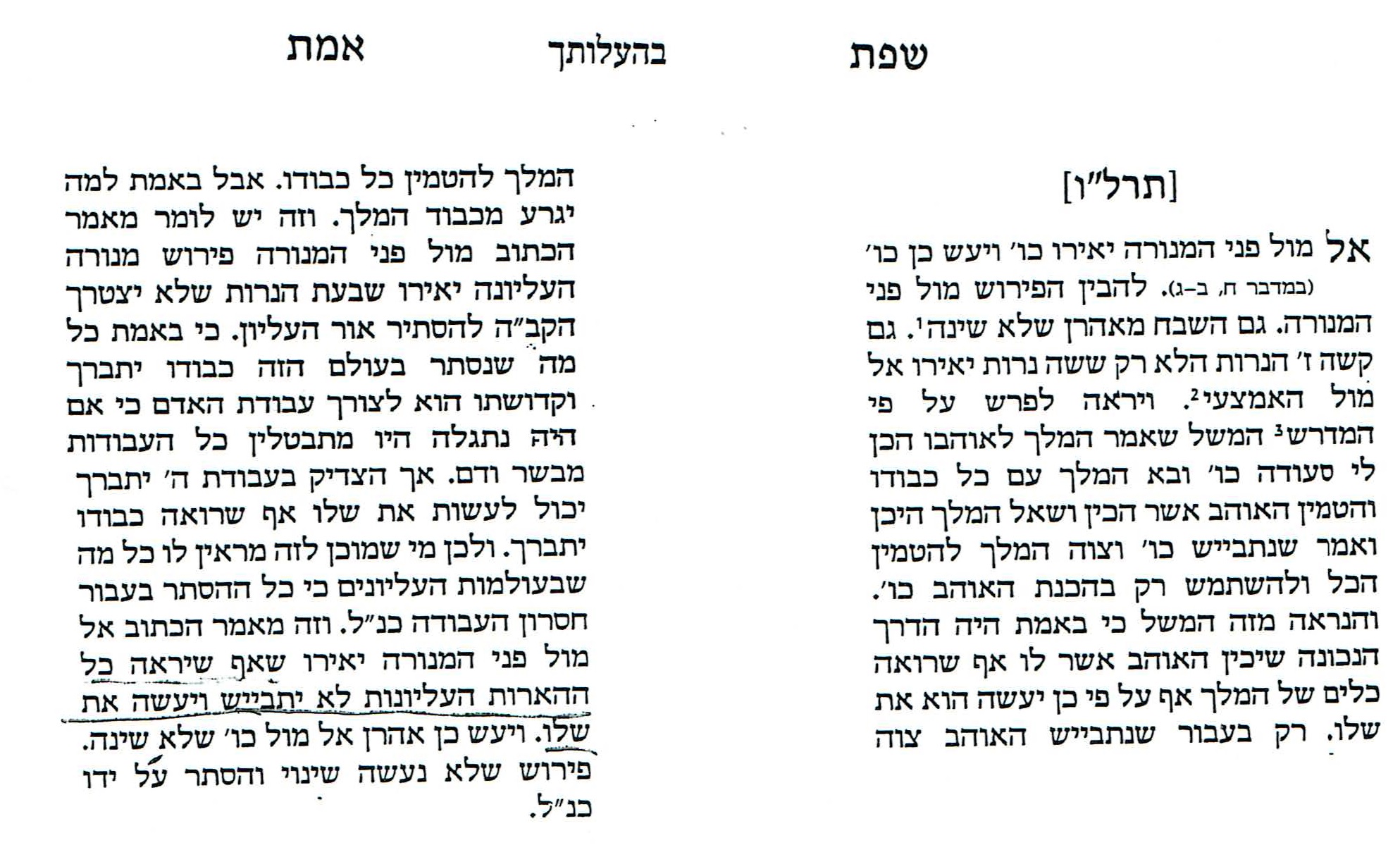

Turn to Page 3. I’m sorry that in the great Chasidic world, there are many great Chasidic writings that have not been translated. One of the great Chasidic writings that have not been translated is the Gerer Rebbe’s teaching. The Gerrer Rebbe’s teachings is — it was a city of Ger in Poland. The second Gerrer Rebbe’s name was Yehuda Aryeh Leib. They took it from his writings after he passed away and what they took from his writings and he passed away, they called it the Sefat Emet because he wrote little pieces every — they found the years. Based on the years. He started to write it in the early Taf-Reish-Lamed, early 1870s. He goes into the early 1900s, a 30-40-year period of writing. Little pieces on each week. There are beautiful little pieces.

On this week’s Torah portion of Beha’alotecha, he quotes the Midrash. He works with that beautiful example. But he takes the Midrash and changes it up. What does he do with the Midrash. He quotes the whole Midrash, but then he says but I want to tell you something. That the servant turns around and resets his food again and he was not embarrassed. He doesn’t know why G-d appreciates it, but he resets the table and he doesn’t change this time from what the king wanted the meal. Lo shina. When it says that Aaron lit the menorah, it says kein asa, he did that. Rashi says that he didn’t change. The Sefat Emet translates that what do you mean Aaron didn’t change? That he wasn’t embarrassed. He said if this is what the king wants then I’ll reset the table. And he didn’t change from what the king wanted. Here comes a Sefat Emet that says one second. I know that Aaron doesn’t understand what a candelabra has to do with the whole thing, but he did it. The Sefat Emet goes away from the Midrashic a little bit and says I know what the Midrash says and the Midrash ends up with just talking about how the king wants, but I’m telling you let’s go back to Aaron as well and say that Aaron did it. You know what, the beauty of it is that he didn’t change. Although there’s so much going on beyond what he’s doing and he doesn’t begin to understand why he’s doing it, but he did it. Which is a little bit giving a sense what the hand of a person plays a role.

Now, I tell you — I promise you this. I don’t know it for a fact. Give me a time and I’ll get the fact. The Rebbe would take this Midrash, listen to the Sefat Emet and then go one step further and say one second, no, no, no. not only didn’t Aaron change over from what he was asked, to the contrary, he understood that with all those great lights out there, it’s nothing compared to what a human being light a candle. You can’t even begin to compare. That human action in this finite world. The spiritual worlds are looking with jealousy and saying oh my god, look at the uniqueness of a human being’s act in performing a mitzvah.

We don’t begin to understand what a relationship with G-d is because we don’t have that type of relationship. There is an unbelievable significance that the Rebbe lived with that he wasn’t apologetic about what we humans are doing. He moved away from the apologetic language. He moved into proactive language in the uniqueness of a human being’s relationship with G-d. Therefore, with the Midrash, even with the Sefat Emet’s interpretation, we’re still apologetic. We’re not understanding the holiness and the significance of the human being’s act. To the Rebbe, that’s it. Don’t be apologetic. There’s such holiness to that act of a human being, the human touch, that why would Aaron be embarrassed. To the contrary, the Rebbe would turn around and say you wonder why G-d mentions a little candelabra after all the great light of all the spiritual descending of G-d, that’s the point. That all that spirituality of light that’s descending doesn’t even begin to reach the simple light of a candle, of a human being. That’s exactly why G-d juxtapositions the two. All great celebrations of all this great spiritual wealth that’s descending over the 12 days of inauguration doesn’t reach the simple act of a human being lighting a candle. It turned the whole thing on its head. That’s how the Rebbe would view this. He would move it entirely away. That the human act needs to apologize to all the spiritual worlds that are so much holier and G-dlier.

You ask yourself in embarrassment why am I even lighting the candle. Like in the Midrash, I’m going to hide my little schmaltz herring. How can I even begin to match? The Midrash is all apologetic. At the end of the day, the Midrash just simply says that G-d wants it. But you remain apologetic. The Sefat Emet later on says no, no, no, let’s do it even better. Just do it because you have to do it. Give you credit for doing it.

The Rebbe says no, don’t go there. Understand that, to the contrary, he would turn everything over and turn around and say it’s behooving upon us to understand that in that simple menorah lighting, G-d is willing to juxtaposition that simple lighting of a candle, of a human being, to the entire spiritual wealth of 12 days of celebration.

Audience Member: The commentary from Rav Hertz on the parsha, the lighting of the menorah, he says this was the only thing that was left over after the destruction of the second temple and you see it now (inaudible).

Rabbi Alter Bukiet: Yeah. He’s based on Nachmonides. Nachmonides in the beginning of this week’s Torah portion speaks about why did G-d juxtaposition the mitzvah of the menorah versus other mitzvoth that were in the temple. He goes down this path because the menorah survived beyond the temple. That’s another whole idea.

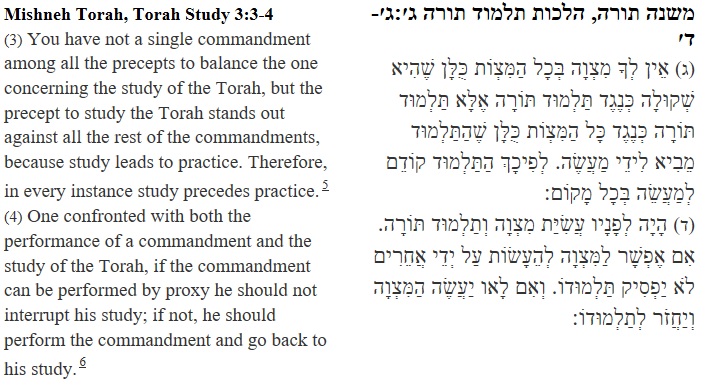

I want to end this class with something that I brought up a couple of weeks ago. I don’t know if it was in a class. I don’t know if it was at a speech. But I want to tie it in so you’ll see the Rebbe in his real glory, in this whole idea. There was a man by the name of Yitzchak Yaakov Weiss. He was born back there in Ukraine, in Galicia. The borders kept on moving around so I can’t even tell you if it was part of Ukraine or part of Galicia. He ended up going to Munkatch in his youth in the ’20s and he became very attached to the Minchas Elozor, R’ Chaim Eliezer Shapiro, the Munkatcher Rebbe. He actually gave him his semicha. Then this great man, Yitzchak Yaakov Weiss, moved on through World War II, ended up for a while in the city in Galicia being a rabbi, then got hired in Manchester, England. He became a big rabbi in Manchester, England. It was around 1970 that one of the leading rabbis of the Hungarian charedi world in Jerusalem passed away and they hired him. They brought him over from Manchester, England and he passed away in 1988. So the last 18 years of his life, he was one of the leading authorities. His writings were Sha’alos u’Teshuvos Minchas Yitzchak. He was this Hungarian great halachic authority. Really one of the leading authorities. Many people read his writings on law because he was a brilliant scholar.

He never met the Rebbe. He had an only child, Leibish, and Leibish today is the head of the Satmar community in Manchester, England and a scholar in his own rights. Leibish helped put out his father’s writings. Recently, Leibish tells a story. If you don’t know the story behind the story, you wouldn’t pick up on it. He says like this.

My father, if you look at his third volume in his writing, Minchas Yitzchak, his writings on Jewish law, was asked a question. There was a patient in Hadassah hospital that was put into quarantine and whatever the patient touches, when he leaves, gets burned. From sheets to blankets to pillows, pajamas. Whatever he touches gets burned. He was a religious man and he was going to be in quarantine for 10 days. The question became should he be putting on tefilin because the tefilin after the 10 days was going to be burned. The doctor said to him, we’ve got no choice in the matter. You want your pair of tefilin, you can have your pair of tefilin, but it’s not leaving this room. It’s going to be burned with everything else that has to be burned. Like majority of authorities, he ruled along the lines that he should not be putting on tefilin. Respect of the tefilin that will be burned after 10 days, don’t put on the tefilin.

Volume 4 of this man’s writing comes out two-three years later and in Volume 4 in the back, he says I want to revisit one of the previous decisions I made about a person in quarantine. He says I’m revisiting it due to somebody who I consider important. Who I read of his writing and realized that I should rethink my position. Therefore, I say that the person who wants the tefilin should be allowed to put on tefilin although the tefilin will be burned. The son says in the writing in Volume 4, he doesn’t say who was this person, what was the writing. It was the Rebbe, the son says.

He says he read from the Rebbe that the Rebbe questioned that the soul of a person who was nurtured by a mitzvah and needs the mitzvah for not only his mental spiritual health, but even for his physical health because he’s connected and now you have the object of the mitzvah, should you not protect the person over the object. Therefore, the Rebbe — I’m running past my time so I’m not going to show you the Talmud and all that, but take my word, the Rebbe bases it on a Talmud, not directly perfect, but off the Talmud. To the Rebbe, the human touch of the human being performing the mitzvah is greater than the mitzvah in its own objective reality.

The mitzvah, in its own objective reality, why should it get burned? Why should a human being take the mitzvah and change it? Comes the Rebbe and says no. That the significance of a human being performing the mitzvah supersedes the mitzvah in its own right. In that relation of doing the mitzvah, although it’s only for the next 10 days, makes a difference. That moment of a human being touching a mitzvah takes the mitzvah to a place where the mitzvah on its own can’t go. Don’t take it away. All of a sudden, the Rebbe turned around and said allow him to wear the tefilin. This man was not Lubavitch in any way. His son is the head of the Satmar community in Manchester. But this man turned around and said I have to listen to this. I’ve got to move myself away from a position where I just was more worshipping the object of the mitzvah and not understanding the significance of what a person does to the mitzvah and where the person can take the mitzvah which is beyond the mitzvah itself. You’re depriving the pair of tefilin from that human being wearing it for 10 days and not only are you depriving the person, you’re depriving the whole mitzvah of tefilin to not having that experience done to it which is beyond the mitzvah itself.

(END RECORDING – 01:07:53)

CERTIFICATE OF TRANSCRIPT

I, ROCHEL BADDIEL, as the Official Transcriber, hereby certify that the attached transcript labeled: REBBE’S VISION – THE HUMAN TOUCH (RABBI MENACHEM MENDEL SCHNEERSON was held as herein appears and that this is the original transcript thereof and that the statements that appear in this transcript were transcribed by me to the best of my ability.

| Category | Religion, Judaic Studies |

| Tag | 12th Grade, Adult Education, College/University, Homeschool, Informal Education |

Write a Review

Leave a reply Cancel reply